Trent Peterson on The Wild In Us

To say that I’ve been inspired by the stories and photos of Trent living true to his mission is a grand understatement. I trust that you will also find more than inspiration in hearing about his lifestyle, and what led him to find his calling.

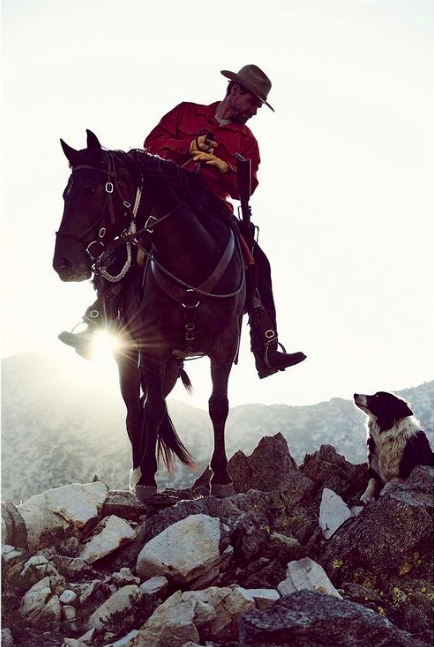

Trent is a modern-day wilderness packer, saddle maker, and adventurer, whose explorations in the wilderness with horses and mules are the stuff of western classics. While inspiring others to embrace the call of the wild through his business The Wild In Us, Trent gives back to the National Ataxia Foundation, which funds research for a cure to the hereditary disease, and supports families affected by it.

In 2017, Trent completed the Pacific Crest Trail on horseback, riding from Mexico to Canada to raise awareness about Ataxia, and the plight of wild horses, as he adopted and gentled previously untouched BLM mustangs for the trip.

Today Trent continues to explore wild areas through packing, and hand-makes fine leather goods in his saddle shop, donating a portion of proceeds from his creations to the National Ataxia Foundation.

Read on to learn about the drive to turn hardship into inspiration, what it takes to gentle wild horses, and the importance of eliminating the word “can’t” from your vocabulary.

Photo by Jay Kolsch (@jaykolsch)

Tell us about yourself and the work that you do.

I’m the owner and founder of The Wild In Us, which is a saddle shop, a business that happened kind of out of necessity. It’s a way to continually give to the National Ataxia Foundation by donating 3% of my sales from the shop to the foundation, which funds research into the disease, and also helps provide families with beds and wheelchairs, and whatever they need to live out their life with the complication of Ataxia.

Ataxia only affects about 1 in 100,000 people worldwide. So it’s a very small group of people that are affected by it. And that’s a problem really, is that for big pharma, there’s no money in the research, like your cancer or your MS, or anything like that where you have a higher rate of infection or people carrying that genetic defect. So they just kind of overlook it, and you get pushed to the side and say, “deal with it.”

There are a handful, or two pharmaceutical [companies]—one is Tekada, which is a Japanese based pharmaceutical company. And they are pretty much the only ones, other than the universities, that are doing any kind of study and research into this. Tekada is not a profit based pharmaceutical company. They don’t care, they just find those weird and obscure diseases, and they’ll go down the rabbit hole, and spend all the money they need to. So it’s pretty cool. But a lot of that research money comes from foundations like the National Ataxia Foundation, which helps direct moneys that they raise to fund those research projects.

Do you have an idea now (3 years later) if there’s any more progress made in the research for a cure?

Yeah, there has been in the last 3 years, some pretty big leaps and milestones that were hit. What they are able to do is using what they know from MS, to not cure it, not get rid of it, but stop it. They are having a lot of success with that. They had huge success in trials with mice and whatnot, but they went into human trials 3 years ago for the first time, with a pill, and it’s showing some good progress. But it’s still a long way out. Honestly, in my lifetime if we see a cure, I’ll be stoked. But it’s just those things that move at such a snails pace, because there’s so few people that they can take who can try this.

“There’s a very real possibility that I could come down with it, or have the gene, and my life would be over. So today I’m going to live as if I’m going to die tomorrow.”

Can you talk a little about how your fathers memory informed your mission?

When Dad passed away, to kind of give a bit of backstory as to how and why The Wild In Us was born, it was an 18 year struggle, if you will, from the time that he was diagnosed to his death, and just slowly watching his life get stolen away. He was trapped inside of his body, in his own prison, just over time. Because mentally, you’re still 100% there, but your body just isn’t there. There’s a disconnect between the neurons. So it was a really agonizing thing to watch, but that also gave huge inspiration to my life. That could be me. There’s a very real possibility that I could come down with it, or have the gene, and my life would be over. So today I’m going to live as if I’m going to die tomorrow. I made that choice at a really, really young age. As soon as Dad really started to not be able to walk. You know, he was tripping all the time. We couldn’t go hunting, he couldn’t ride his motorcycle, he couldn’t do anything. He was becoming more and more confined to the house, and that was when I made that choice. So when he passed away, even though it was excruciatingly painful to watch and observe, there was a sense of joy, and release, and relief in knowing he had passed away. And that was when I had watched the shooting star, (I think I’d spoken about it in one of my blogs), but with Orion, and why this constellation is so important to me was watching that shooting star go from Orion to Pleiades, was awesome, like he got what he wanted, he got his freedom. I was totally prepared to just say goodbye, just check out, jump on my horse, and not know where I was going. I remember talking to my farrier and I was getting a new set of shoes, and figuring within a couple of weeks I was going to just leave. Didn’t know where I was going, just off a direction. And he asked me “Why? What is that going to accomplish?” I told him I don’t know, and selfishly, I just feel like I need to go. And I thought about that more and more in the weeks after, and that’s when it dawned back onto me that Dad always told us that “Whatever you do, do it with a purpose.” Don’t do something just to do it; have a goal. And so I put that on the shelf and said, “how can I make this urge in me meaningful and leave an impact?” It was through the PCT that I was like, OK, this could work.

This was before Unbranded had come out or anything. I just kind of went down that rabbit hole, of how many different ways can I create conversation with total strangers? And that was where the mustangs came in. Here, I’ll take 3 mustangs, and I’ll ride from Mexico to Canada, because you’re guaranteed to see thousands of people going “what are you doing? Where are you going?” [laughs]. And that was how the conversation was started with educating people on Ataxia. That was how was it all kind of came together, was needing a vehicle to have that conversation with people.

The PCT was the way, and kind of the perfect time in life as well, where being a winemaker and a viticulturist at the time, I was beginning to see the end of that path in my life. I wanted to deviate and get away from it. It had fulfilled its purpose with me. I just took the fork in the road basically. Said, OK, I can continue on being a winemaker, doing this, and it’s easy, it’s make good money, or I can go off and start this project, with no idea of the impact it’s going to have. So I just quit; called my boss and I said “I’m out.” And then within a month of that, I was at the BLM holding facility checking out mustangs. A friend of mine had a ranch down there in Susanville, California, which was right next to the holding facilities for the mustangs, and that was where I was going to train them. I basically just moved down there in my camper trailer for 3 months, and didn’t do anything, just had some savings I was living off of. Living there for free, expenses were pretty low. Then I started to Go-Fund Me which was to help generate the financial backing to be able to ride a horse from Mexico to Canada. Because initially when I first started looking into it, I was like, oh yeah I can totally do this for what, $5,000 USD or something. No [laughs], not even close. Realistically to be able to do it, you need about $15,000 USD. You know because you’ve got 3 animals you’ve got to feed; that was the hugest thing. Before then, I just had my one horse, so that was easy enough. But feeding three animals for a year, that adds up real quick. And on the trail as well.

Pretty quickly, I was able to raise money for that through the community that formed around it. And then with that, came the sponsorships for companies that wanted to get on board. And then, the real need for a saddle, which is what I do now, and had been living in my head for so long, became apparent. Because [with] the saddle I was riding in, there was no way it was going to make that journey. So here’s another fork in the road. Let’s just tackle this. I had gone to a saddle maker and said "Hey, this is what I want, here’s my drawings”, [and asked] “how much?” And I couldn’t afford that, so I was like, I might as well just make it myself. That’s where, when I say it was out of necessity when I started the saddle shop, was because I couldn’t afford to pay somebody to build me it. So I built it myself. When I finished the ride, people saw that saddle and they were like “that’s pretty cool. I’ve never seen that before. Can you make me one?” and I said “sure why not”, and I made another one, and another one. And in my brain I’m like “how am I going to continue this Wild In Us project now that I’ve finished the PCT, and I accomplished my goals, and I’m like “Ahh! that’s it.” Three percent of $4,000 USD is a pretty good chunk of change. So that was how that happened at the end there in trying to find a way.

Kind of going back to Dad and his life, you know he was not a man who would sit down and lecture you for hours on end on how you should live your life, or what you should be doing, and if he felt like you were slacking or anything like that. But he was the type where he lived his life in a way where you’re like, I want to do that, I want to be like that guy. And if I want to be like that guy, I’ve got to be able to find the way. He’s not just going to pick up that 5 gallon bucket and carry it up the beach for me because it’s easier. No, he’s going to walk by with two 5 gallon buckets and and say “Where there’s a will, there’s a way! Dude get up the hill! I’ve got two, and you’ve got one, so it’s possible.” You know he always showed you that everything was possible as long as you put your mind and your heart to it. That was kind of the building blocks for me in how he raised us. There’s me and my two brothers, and we’re all very, very, very different, but we all have the same outlook on life.

“Out of all the words in our vocabulary, I hate the word ‘can’t’. If I hear somebody say “I can’t do this”, it just makes my blood boil. Because it’s not “I can’t”, it’s “How can I?”

Forming my career path in life, we were sitting there at the kitchen table one time, and I think it was mom who asked it, but she said “Boys, what do you want to do with your life? What do you want to grow up to be?” My dad being a diesel mechanic, you know, as a little kid looking up to his dad, I’m like “I want to be a diesel mechanic.” [Laughs] But my dad’s like “Bullshit you are! You’re not going to do that; you’re going to find your own path.” He didn’t force onto us that we had to go to university or something like that. If we went that way, great, but if we wanted to continue working with our hands, awesome. But it’s not going to be what I do, you’re going to do something else. You’re going to live your own life. And so that really changed what I wanted to do, and what I thought my expectations were supposed to be for what I was to get out of life. So it’s been one thing after another of doing something different. You know, always trying broaden that horizon of adventure.

Your stories really read as you came into this planet as a natural-born adventurer. Doing things that are not for the faint of heart.

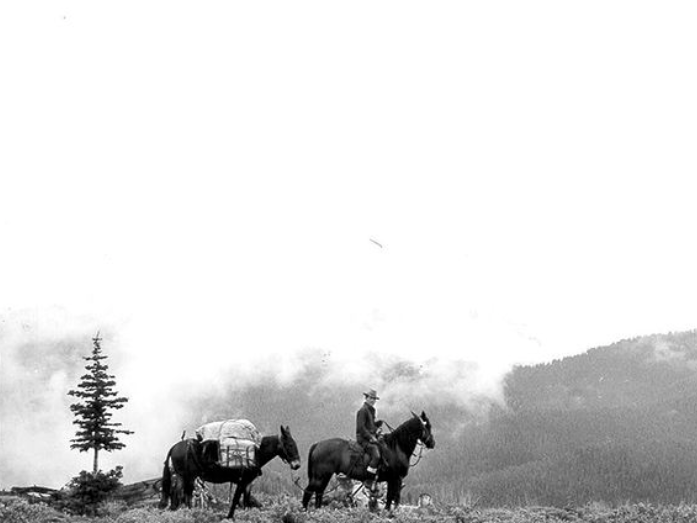

You know, I don’t know if it’s the faint of heart, or that we all have became a little bit too used to our comforts. Everybody can have the same adventures. It doesn't matter who you are, where you come from, your body type. There was that one guy (@secondchancehiker) who was like 400 lbs. Anyone walking down the street would go “oh, well that guy is going to do nothing with his life”, and then he made that choice. Because that’s everything. Happiness is a choice. It’s not something that’s just given to you. You choose to be happy. And he just decided to say, “you know what that’s not what I want for me. I want a better life.” So he formed it, and now he’s lost an insane amount of weight, and he’s off doing everything. A lot of that comes back to just dramatically lowering your expectations of what a day-to-day life should be. We all think that we should be living this lavish lifestyle, being surrounded by technology constantly, climbing into bed with a down comforter, and all these things and that’s what life is. These things that money has bought you. But really when you step back and you take a look at it, absolutely not. Did our ancestors have those things? No, absolutely not. What did they do? They slept on the ground. They ate really simple, basic foods, and they seasoned it with hunger. So lower those expectations, and everything becomes possible, because everything is up from there.

When I got on the trail, and through packing, that was one of the earliest things that I learned from that. Yeah it can be uncomfortable at times, but it’s only uncomfortable because I think I should be more comfortable.

Photo by Jay Kolsch (@jaykolsch)

To someone who has no experience outdoors, let alone experience with horses, and saw your photos and stories, and decided they wanted to do something like that, what advise would you give? How would you tell them to get started?

With the word “Yes”. Simple as that. Out of all the words in our vocabulary, I hate the word “can’t”. If I hear somebody say “I can’t do this”, it just makes my blood boil. Because it’s not “I can’t”, it’s “how can I?” And if a horses, mules, or packing is something that’s really attracting to you, and you want to get into that, just simply ask somebody. One of the things that we have become is so shy. People live behind their screens now, in this really comfortable zone where we can see the pretty pictures, but we are afraid to simply ask somebody that knows more. With our whole world of horses and packing, yes there’s clinicians, yes there’s books, and DVD’s that will teach you everything you need to know, or think you need to know under the stars. But really what has allowed this way of life to continue, is through the sharing of the knowledge. I don’t think I’ve ever met a single horse person who turned away somebody who said, “hey I want to learn this.” If you legitimately want to learn it, you’re committed to it, then I’m going to pass on every bit of information I have, because that’s what the people that have come before me have done through me. That’s how we carry this on, by passing it on. We don’t own this knowledge, it’s all shared.

So I just would encourage you to pick up the phone or drive up that driveway, or stop that person that’s riding down the trail. Just ask “can I follow you along?” You know, just strike up that conversation, and if they’re a good match for you, and you feel like they’re treating the animals with respect, just learn from that person through shadowing, and dedicate some time. We all have on average 40 hours a week that we dedicate to our 9 to 5 jobs, but what are you going to do with the rest of that time? Watch TV? No. Go muck a stall. Get involved with the horses. Horses being the size that they are, you know that’s a 1,200 lb. animal that if it wants to, it can destroy you. But understanding their energy, and how they communicate, and you being comfortable, the only way you’re going to do that is through exposure. Yeah you can watch those DVD’s and learn how to in theory round pen an animal, and hopefully get to be able to pick them up, but unless you’re around them, and observing them, you’re not going to be truly comfortable with them. And until your energy level drops to where you’re comfortable, you’re never going to connect with them on a level that you need to to be able to do that things that myself and others do.

“That’s how we carry this on, by passing it on. We don’t own this knowledge, it’s all shared.”

The people that already own horses ask me that same question, “how can I do what you do?” And I just simply ask them that is [their] feeding schedule like. [They respond] “I get up and I throw two flakes in the morning, muck out a stall, go to work, and I come home, throw two flakes in the evening, muck out the stall, and go inside and make dinner.” But very few people understand the value of when you throw that feed in there, hang out with them. Stay with them for the whole time that they’re eating that food. Because you’re now becoming part of their herd, and you’re observing them in a very relaxed state. And they’ll do things for you more willingly, than if you were just chucking them food. I mean why would you want to go hang out with somebody when all they do is chuck you food, then go grab you, and make you go to work? Right? They’re not going to want to do that. It’s a bond, it’s a partnership, it’s a union. We don’t break these animals. We don’t crush their spirits, and force them into machines. That was the old way of doing it, for sure. But we can develop a relationship with them, just simply by hanging out with them, and being with them.

Going back to finding that person who has animals and you want to be around it, offer up your time to go feed them, and then hang out with them. Don’t overcomplicate it. Keep it simple, stupid [laughs]. Just start off with the simple things, and get yourself centered and right, and comfortable around them. Then, go up from there.

Too often, I get people who come to the pack station, and they don’t do all the steps through “x, y, and z”. They just want to jump straight to “z”. They show up to the pack station, and I’m like “OK, well we’ve got to take this load over the pass. I’ve taught you all your knots and hitches, and you got that down, so let’s kick a leg over and go.” And their hands are shaking just to bridle the animal. So there’s no point in knowing this information that I just taught you until you can go bridle that animal without being afraid of it. Do that first. Get that right, and then learn all the other glorious and glamorous things that make for pretty pictures [laughs].

The age of social media has allowed us to see a beautiful 10-second video or clip of someone on a mountain with their horse, but we don’t think of how many hours were spent to get to that point. And that it’s not so much you, but the relationship you have with that animal.

Social media has been one of those things, like a “devil wears Prada.” It’s an evil thing in disguise. It is a really wonderful thing [at the same time], it’s something that in this day in age for me business wise, for a few minutes out of my day, it generates business for me, and hopefully inspires a few people. As social media has increased, there has been a huge, huge, huge uptick in people going out into the wild, because they see those photos and they get inspired and go do it. But very real is what you said: people don’t realize how many hours or years it’s taken to get to this place with this animal.

You know like Minarette, when I was training him I was convinced he was going to be an impossible horse. That he was destined to be a pack animal, and that was it. There was one point where I just threw my hands up and said “I’m done with you dude.” And it was at that point when he broke me down, then he changed. It was literally the next day. I came to the corral and he kind of looked at me, he’s like “OK, now that you’re at ground zero, let’s climb up together.” And I was still not totally convinced with him. Until, it was in the Feather River in Northern California, dropping down to the Feather River there, that was the day I very viscerally heard him speak to me in my head. I was frustrated, we’d been cutting trees all day long, and we had another tree to get over and he refused. I said “Screw it dude”, and I threw the rains up and said, “You figure this out; [pointing] we have to go that way.” He walked back the trail about 15 feet, [I thought] “You’re not going to just walk back to last night’s camp, are you? Because that’s going to suck. It’s like 30 miles that way.” [Laughs] He stops about 10-15 feet, turns and looks down the trail, and he looked at me. I swear to god he said “over here you idiot.” So I walk over there, and sure enough, there was this bypass trail that went down and around the tree and came back up, that I didn’t see when we went by because I was just looking forward. But he saw, and he was just like “I’m not going to jump that stupid thing when there’s a trail right here!” And that’s when he became my life partner. But [it took] months and months and months to get to that point [laughs]!

“…the real reason why I work with mustangs is we as humans breed horses for certain disciplines, and we’ve been doing that for thousands of years. We’ve created some pretty magnificent animals, but there’s only one thing in this world that truly, truly can create something that deserves to be here, and that’s Mother Nature. She’s brutally honest.”

Instead of getting an already trained horse that you know could make the PCT trip, why go through all that effort to gentle mustangs? What is the gentling process like for you?

Mustangs have a plight of their own for sure. Being managed by the federal government, by the BLM, and they’re on the open range and they’re competing with the cattle industry, they’re competing with the antelope, competing with the deer, and they’re competing with the natural ecosystem that they didn’t evolve with. So you have all that, but the real reason why I work with mustangs is we as humans breed horses for certain disciplines, and we’ve been doing that for thousands of years. We’ve created some pretty magnificent animals, but there’s only one thing in this world that truly, truly can create something that deserves to be here, and that’s Mother Nature. She’s brutally honest. It’s either live or die. That’s it, there’s nothing in between. And so over the last 500 years, she’s been doing that with the mustang. So why would I want to take something into the wild, and on a journey like that, that I think because of what we’ve done and we think that we have the best insight to the best suited animal? I know nothing; I am not qualified for those decisions whatsoever. Nope, zero. I leave that to Mother Nature. That’s where the mustang speaks to me. The only contribution that we’ve done to it is when the Spaniards decided to go home, and they left them behind. That was it. The rest has been up to Mother Nature. So when I’m thinking about going over a mountain pass, or looking down the PCT, learning that trail and what kind of environments I’m going to be in, I want that animal that can go 40 miles across the Mojave desert without a drop of water, and be OK. Because anything less would be kind of unfair. You basically got two kids, the kid from outward bound, inner city that can kind of get through it, but are they going to be comfortable? No. Versus the kid that grew up in a log cabin off the grid, in the middle of nowhere. That’s the one that’s actually going to do the thing. That’s our two avenues that we’ve done in life [as humans].

The other thing [with the mustang], is working with mules and knowing how it doesn’t want to see your application, it wants to see your resume; it wants to know everything about you, and uses it’s mind. You can’t force it into doing something. If you try doing that, it’s just going to stonewall you and shut down. You have to have a conversation and come up with that idea together, and develop that friendship. Well I see that in the mustang; the mustang is the same way. They don’t have someone bringing food twice a day to them, cleaning out their stalls, taking care of them, being super domesticated and becoming kind of soft. And so they constantly have to be thinking “Well, is that going to kill me? Or can I fight it? Or do I need to worry about it?” I’m going to think about all these things before I do something, because of the environment that I live in; if I make the wrong choice, I’m going to die. So you now have an animal that things, and when you’re into those really bad situations, you can give them the reins and say “I need your help on this one.” And you see those gears turning inside their head, and they’re figuring it out, going “OK let’s do this option. It’s going to save us both.” Because they have self-preservation, of course. They don’t want to die. They don’t want to fall off that cliff any more than you do. Whereas I’ve literally had my quarter horse [laughs] walking straight [off a cliff]… I told him to go straight and that’s what he was going to do! Whereas with a mustang or a mule, no, they’re just going to stop and go, “you’re out of your goddamn mind! I ain’t going to do that.”

“It takes as long as it takes. You go in, and it could take 15 minutes and you’re done for the day. It could take 3 hours, and you’ve still not gotten anywhere. It just totally depends, but always keeping in mind that it’s a conversation. It’s nothing that we’re ever going to force them to do, because then they’re not going to be reliable, they may not be as willing to do something that you ask of them.”

So that gentling process, once you get beyond that initial fearful state, because you go into taking this wild animal where it has to make a decision every day, [asking itself] “Is it going to kill me? Or do I kill it? Or do I run away?” Now I’ve taken that animal from the wild, put it into this small confined area, and I get inside there. It thinks, “Do I need to kill this thing? Is it going to kill me? Well I can’t run away, so it’s either kill or be killed.” But through understanding of their language, which is through observation of their natural state and their herd, you can begin to have that real quiet conversation. Once you’ve had that acknowledgement that “I hear you; I listen to what you’re saying, and I respect you”, then everything begins to change after that. Because once they’ve gotten that respect from you, then they’ll give it in return. Because I’m a predator and they’re prey, so I have to kind of mentally put myself down, and put them up, in the ladder or scale of life, because I need them to understand that I’m not here to hurt you. I want to be your friend. And then once I’ve done that, and I haven’t even touched the animal at this point, (this is all just in body language), once that process has been achieved and now I’m communicating with them, then I can really start the gentling process through touch and making that first contact. None of this is rushed. It takes as long as it takes. You go in, and it could take 15 minutes and you’re done for the day. It could take 3 hours, and you’ve still not gotten anywhere. It just totally depends, but always keeping in mind that it’s a conversation. It’s nothing that we’re ever going to force them to do, because then they’re not going to be reliable, they may not be as willing to do something that you ask of them. So just giving them that space and that time to check in with themselves, [and determine] this guy’s OK. He might look like a mountain lion, but he’s not going to pounce on me like a mountain lion.

You see often where people will go into that round pen and they’ve got that flag, and the first thing they do is just start chasing the animal. Like we’ve got to get a good lather going before they listen to you. No, they’re just giving up. That’s what they’re doing. So when those moments happen, or that moment where you’re like “Aha! Now we’re listening to each other”, that’s pretty cool. It’s a pretty magical event that happens, and you just have to allow that space to happen.

Going out into the wilderness with the mustangs you gentled, would you say that you earned an extra layer of trust and bond that you couldn’t get otherwise?

Oh for sure. Yeah, when you live on the trail with a mustang or a mule, you definitely develop a different relationship. Not to say that it’s anything less than if you didn’t do that. But it’s something tangible. You’ve really gotten to a level of understanding with them and connection with them that I don’t get with other animals that have never been out on that trail, and that are in a corral and they go to a round pen or to be ridden in an arena. And I might take them out for a day ride or something like that. But when you’re out there, 3 days away from anything, you’re looking after them, they’re looking after you. You are going to for sure develop a different relationship with them, if you never had done that. Like Minaret now, he never lives on a high line. He’s just loose. It’s always the joke at the pack station is that I’ll have a halter hanging from the high line so if I need to clip him to it I can, but he just hangs out. I’ve woken up multiple times with him laying next to me on my bed roll.

That bond really begins to form when you’ve worked hard all day long. You’ve done 20, 25 miles, and you make your camp and get that release. You let them loose in the meadow [or campsite] overnight, and now they get to go be a horse, to go roll around, and their job is done. So they’re putting in a hard day’s worth of work and being massively rewarded for it. So inevitably there’s something that’s going to happen there. You’d have to be kind of, pretty numb as a human for that not to happen [laughs].

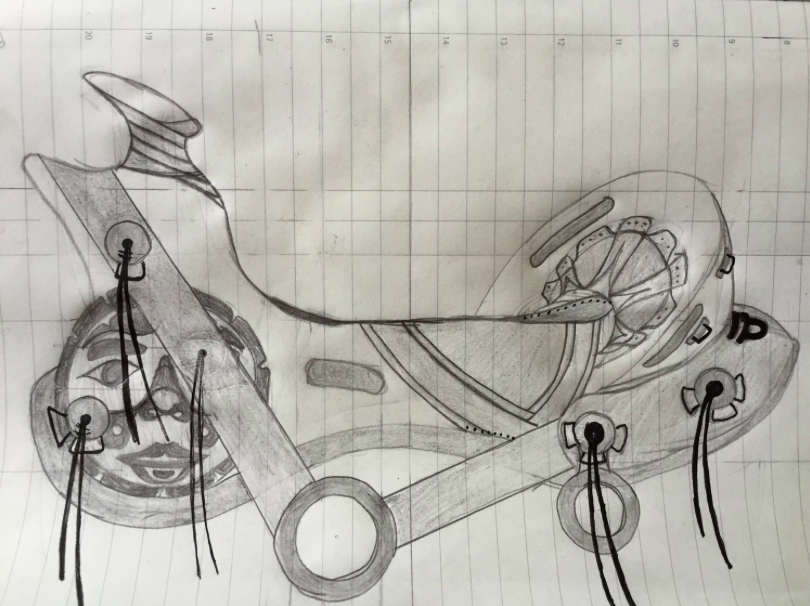

As far as saddle making goes, how did you design the packing saddle that you used on your PCT ride? And how has the packing saddle evolved since then?

There hasn’t been much alterations; there’s a few little things I changed in the saddle, but it’s kind of stayed the same from the first one I built. The way I came to that design, and how I felt like this was what I needed, was years and years of riding different saddles. I had a slick fork wade, I’ve had an Australian saddle, I’ve ridden in a McClellan saddle, and I rode in an old bronc saddle at one point. Because of my dad being a mechanic, I think always having that mechanical engineering mind, everything I look at I wonder, “How was that made?” And having ridden so many different saddles, you get one and you ride it and you think, “OK I like this, but I don’t like that.” So then I would just make a mental note about that, and then I would try a different type of saddle. And I got frustrated with not being able to find that saddle that fit the bill. I like the light weight of the Australian saddle, because for me, ethically I don’t believe I could put a 55 lb. saddle on an animal, and then put my 180 lb. body up there—my slicker, my saddle bags, and everything. All of a sudden, you’ve got way more weight than you’d ever put on a pack mule, on your horse. And you’re saying “Let’s go.” But then, the Australian is not very structurally sound, you know for the kind of riding in life that we do here, it’s just going to fall apart.

So, like I said I just kept making mental notes, and then finally just put pen to paper and started drawing it out, variations of it. And this is all stuff that, without being a saddle maker, I didn’t know, and was probably the success to coming up with the design, was I didn’t have those limitations put on by a traditionalist saddle maker, saying “No, we don’t do it this way; we do it that way.” Well why? When I called up Trevor O’ Ferrall, a friend of mine who is a saddle maker, I said “I’ve got this idea. Can you help me with it?” And he said yeah, come in and use my shop. I showed up with my sketches and drawings and we started making patterns. I think we spent a week building that first saddle, and five or six times a day, he’d get to doing something, and I’d say “What are you doing?” [And he’d reply] “Oh, going to scratch this because we’re going to put the seat here.” [I’d say] “No we’re not; I want to do it this way.” [He would say] “I’ve never seen it done that way.” Well, exactly [laughs] that’s why were doing this thing! He had to kind of let go of those traditional teachings he had from my coming in there with blind faith that we could do this, and never had done it before. We built the thing, and it hit the mark. It did the job, and that’s why I haven’t really changed it much. It took about 5 years to come up with it in my head, and then proving it on the trail, that was the big deal. I did some packing with it in the summer before, and then got on the trail with it, and proved it, that it does work.

“…just take a step back and you look in the timeframe of the West, you go back to before barbed wire was invented, that’s where you had really light, bare boned skeleton rigged saddles. Because these were men and women that lived out of their saddle. And when you’re living a life with your equine, you’ve got to be fair to them, and having these giant 55 lb. saddles dry, that’s not practical.”

You know, the mustangs and the saddle were in almost the same boat, because the mustangs, yes they were gentle, yes I could ride them, but did they learn everything that they do? No, absolutely not. We were going to learn it on the trail. Same with the saddle. Was it built well? Was it sound? Was it strong? Absolutely. But we’re going to learn about the thing on the trail. So I made a few tweaks here and there as we went down the trail, but not too much.

It was really about not having some sort of traditional background, I think, that helped form that. And I think that something in my day to day life in the products that I make, some of them are pretty traditional, and other ones are pretty out there, but they fit the need. So that’s why I make them.

Have you gotten feedback from very traditional saddle makers who are critical of your saddle?

Oh, one hundred percent. I’ve been told I’m an idiot, that I don’t know what I’m doing… You know, the big push backs that I get from traditional saddle makers or people that are into traditional saddles is they always say, “I rope big steers. So I need a big, heavy saddle to do that.” To which, if that’s the biggest criticism that you can give about my saddle is because it weighs 19 lbs., and there’s nothing to it, you don’t think you can rope an animal… just take a step back and you look in the timeframe of the West, you go back to before barbed wire was invented, that’s where you had really light, bare boned skeleton rigged saddles. Because these were men and women that lived out of their saddle. And when you’re living a life with your equine, you’ve got to be fair to them, and having these giant 55 lb. saddles dry, that’s not practical. You’re not going to cover the miles you are. So basically, if you need a giant saddle like that to be able to rope a big ol’ steer, then you need to be a better rider. Roping something is down to your balance and your seat, and off-setting that weight. You look at the heat signature of a skirt on a saddle and pressure, it’s not really doing anything. All it’s doing is creating a hotter back. But what it’s providing for us is more leather space to tool and make it look pretty. But as far as staying on the animals back, that one hundred percent on you. Where are you sitting in that seat, how much weight do you have in your stirrups or that sort of stuff.

So that’s the biggest criticism, is breaking that mindset of people that “This is the way it’s always been done. This is the way we do it.” No, it’s only been done this way for a very short period of time in human and equine history. It’s relatively new, so to go forwards we actually have to go backwards. And getting them to break that mindset is where I get any kind of pushback. And I just kind of smile and go OK, that’s cool [laughs]. What you want to think about it, that’s cool, but how did we get to this point? How did we get to this point of time with our saddles and our ability to strap the hides of dead animals on a back and go down the trail? Ok so there is thousands of years to get to this point. Maybe instead of arguing with me about my design, maybe you should open up a history book I guess, and look up how was it done before we had fancy sewing machines, and really advanced tanneries, and guys that all they did was make saddle trees. And all of this amazing stuff that makes what we do really easy, and an ability to make something really pretty. How did we get to that point, and then you might not ask me that same question.

Even go to Argentina and look what they’re riding in. I mean that’s basically a couple straps of leather and some sheep hide. It’s super, super basic, and simple, and weighs less than my saddles. I was just up in Washington in October, hanging with a friend of mine Andy, who is a packer from Mongolia. He had a Swedish military saddle, a Mongolian traditional saddle; they’re all performing the exact same function, but built, put together completely different. There was one common denominator, and that is it was light. It was strong, and it was light. And they’re still used today, by cultures that have not bought into this [holds up iPhone] technology, and decided that our path is the only path. People that are still living the old ways, living that life, the equipment really hasn’t changed at all. They haven’t felt the need to change it, because it works.

Photo by Jay Kolsch (@jaykolsch)

How can we apply this methodology in a bigger way to our lifestyle beyond the tack that we use, or the training that we do?

The biggest thing that I’ve learned, and have taken to heart and come to an understanding to, through this lifestyle of working with leather, tack, and animals, is just simply slowing down. The mindset of 3 miles an hour. That’s the average speed that a horse walks. It’s predictable. I can tell you exactly what time I’m going to be somewhere if you tell me how many miles away it is. We’re just going to go. So if we slow that down,…. in the saddle shop if you try to rush it, if you try to make something really quick, it’s going to show in the final product. We feel that we have to do more, do more, and do more every day. That devalues the product; devalues the result. But if we just slow down, we’ll all get to the same location, the same destination. I might take a little bit longer to get there, but the quality of my existence getting to that point is much richer. I’m going to notice things that you’re not, because you rushed it through. With wine—it was why I couldn’t be in that world anymore—there was always this push for more, more, more. And I’m sorry, but if you want a good tasting bottle of wine, it has to run its course at its own speed. That was ultimately why I left it. So through this way of life, and through this shop, it’s really, really paramount for any kind of success that you wanted, whether you’re training an animal, or you’re just making a simple leather knife sheath. Just slow it down, and you’ll have a much richer product, or a much richer life, or a much richer understanding than you would if you were to try to rush it through and make more of it, or do more of it. Just be satisfied with your results that you get and you achieve, than being satisfied in the volume. Take simple pleasures.

Bottom line I came into this life with nothing, buck naked, and guess what, that it how I’m going to go out of this world. So trying to line our pockets with more money, and volume, and speed and production, that’s only just for a moment. It’s not really going to ultimately change anything. You know, because you’re not going to take it out of this world with you. You’re not going to take that money with you. What I will die with, are much richer memories and stories. That’s all we have at the end, is our stories. So just slow down and get all those little details that others might have missed because they’re trying to race through this world and line their pockets. Just observe, and life is so much richer when you’ve made that mental choice.

To anyone who might be caught in a cycle of depression, negativity, or feel as though life is against them, or maybe got diagnosed with something and feel hopeless, what would you say to give relief or inspiration?

That’s a hard one. That’s a hard one because I’m a little selfish, you know. My happiness is a product of me alone, and so for me, I just want to have the richest life possible. But for somebody that might be suffering from depression, or anxiety, or whatever it is, it’s a lot harder for them to get to that point. But don’t allow the barriers that we as a society put on these ailments to control your life. These are all things that society tells us that you can’t do that. The only person that can stop you from doing something is you, yourself. Now it’s going to be a lot harder for people to get to that point, but you can get there. If you allow space for that to happen. For people that have a hereditary disease that’s going to take away their life, or a mental disorder that might limit them, the only way that you’re going to actually find that happiness is to just ignore what everyone else says, and just get out of your own head. And don’t subscribe to what the modern way of thinking tells us we need to do.

To get somebody to do that, it’s your own demon. You have to fight your own battle. It’s your own life, it’s not anyone else’s life. So you have that choice, “Do I want to live what my doctor tells me my life is going to be like? Or do I want to live my life?” I can’t make that choice for you. Nobody can make that choice for you. Nothing I can say can get you to make that choice. You have to make that step in your own heart, in your own mind, yourself. Some people take longer to make that step, and that’s fine. But at least make that step. Do it, and don’t do it for anybody else. Do it for you.

“What I will die with, are much richer memories and stories. That’s all we have at the end, is our stories. So just slow down and get all those little details that others might have missed because they’re trying to race through this world and line their pockets.”

If you’re living for somebody else, the only person that you’re going to lose is yourself. It’s a struggle for a lot of people. But I think a lot of those struggles are put on there by external influences, by society telling us that “You have a chemical imbalance in your brain, so you can’t do that.” Watch me.

It’s such a complicated one, I don’t think I could come up with a right answer. For me, the biggest thing that I’ve observed with friends that have had some sort of disorder, it’s watching that acceptance of this is my life. It’s not somebody else’s life that makes those changes. And if you have to take medication for something, that’s fine too. If you’ve got depression or anxiety, or whatever that is, for whatever reason that stigma that’s been put onto those ailments, and those limitations, and if they take a medication to correct their chemical imbalance in the brain, they feel like they’re lesser of humans. No you’re not. You just need just this thing—just like I need a cup of coffee every morning to not kill anybody—it’s like a fact of life. We’ve been doing it with plants, for forever. Why do people take echinacea? Because we don’t want to get sick. Whatever it might be, we’ve been consuming plants that most of these chemicals are derived from for thousands and thousands of years. But it wasn’t until we put it into a pill form that it became a stigma.

Any more adventures or experiences you’d like to speak to about The Wild In Us?

It’s not over [laughs]. You know it just goes back to that Robert Frost poem The Road Not Taken, and that has made all the difference. If you do that in your life, it will make all the difference. There’s a few more adventures in the works that are coming up, and a few more projects that I’m working on. Too early to put out there, but they’ll come out when they’re ready and finished. With The Wild In Us, if I inspire at least one person to go and do something that they’ve never done before, or they thought that they couldn’t do, then it’s a success. I just want to inspire those people to do those things by living my life.

Learn more about Trent

Follow Trent’s journey, and learn more about his story, mission, and saddle shop at The Wild In Us, and be sure to follow him on Instagram @the_wild_in_us.